It doesn’t take Sherlock Holmes to root out the motivation behind Google’s latest research finding that advertisers who stop buying paid ads on Google’s search engine lose lots of search engine clicks. So, in this post I’ll take a look at the research to help you navigate your way through the data.

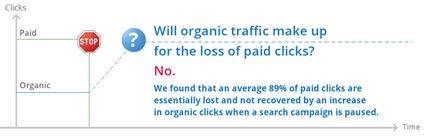

First up, Google’s headline finding:

In the event of pausing a paid ad campaign, “organic traffic does not make up for the loss of paid clicks”

Few should be surprised by this finding. Paid ads on search engines exist to disrupt the natural search flow and provide standout far beyond that afforded by organic listings. And Google has recently enhanced this standout even further with their new Enhanced Ad Sitelinks feature that allow ads to be embedded within ads. So it’s logical that turning off paid ads will result in the loss of the vast majority of clicks they would otherwise have generated. Google’s research puts the lost clicks at 85%, slightly lower than a prior study in July 2011 which claimed 89%. Interestingly, if a minimal paid ad spend is maintained, the

We cannot read any additional data (e.g. click mix between organic and paid listings) because Google’s charts are not drawn to scale and the above 85% actually measures about 66%.

Where ad budgets are partially cut (although the research doesn’t specify by what percentage), the lost clicks amount to 80% on average.

The biggest problem I have with this study is that it assumes all clicks are equal, effectively ignoring the value of the different click types. If, for example, the 80% of lost clicks arising from a budget cut only contributed 10% of the end actions (e.g. purchase, sign-up, trial etc.) then this might yet prove to be ROI beneficial.

We know from prior studies, like Barcelona’s Pompeu Fabra Univertisty’s study in 2010, that search engine users exhibit very different behaviours when confronted by organic and paid ads, and that their propensity to click on either shifts based on their needs. Informational searchers are typically more likely to follow organic listings, while transactional searchers, particularly those in buying mode, are relatively more predisposed to clicking on paid ads.

Google’s study concludes by assessing the % of clicks gained by increasing search advertising spend levels:

Where advertisers were previously not advertising with search ads, and then turned on search ads, the incremental traffic was 79%

No surprise, again, that buying paid ads leads to a sharp increase in overall click volume. However, this comes at the expense of some lost organic clicks, but we cannot gauge how much from the research because the charts have not been drawn to scale.

To accurately assess the true incremental value generated from increasing search ad spend we have to factor in the value of each end action. For examples, if we are seeking informational searchers, who are much more inclined to click organic listings, and by placing additional paid ads we generate fewer organic clicks, the net result may not be positive for our marketing goals.

Google’s report concludes as follows:

Across the board, our findings are consistent: ads drive a very high proportion of incremental traffic – traffic that is not replaced by navigation from organic listings when the ads are turned off or turned down.

It’s hard to disagree with such a generic statement; of course, if you pay for clicks you’ll get more clicks than you might otherwise. But each marketer needs to consider these findings in the light of their unique business challenges. By factoring in the value generated from each type of click, we can make a much more informed judgement about the investment levels needed in search engine advertising to achieve our goals.

Further reading:

- Google’s Research Blog: Search Ads Pause Studies Updates

- Research findings: Infographic

- Google Research Paper July 2011: Incremental Clicks Impact Of Search Advertising (.pdf)