Here are a few key takeaways that I wanted to share with you:

Online social sharing looks set to continue to rise, with more people sharing more things, more frequently. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg thinks that sharing will grow on an exponential curve, doubling roughly every 18 months (per Moore’s Law), but new research suggests that growth may not be guaranteed in the world of sharing.

So, why do people share less over time? Social sharing is a very enticing promise. Being handed the power to instantly share almost anything with almost anyone anywhere is an exciting and liberating proposition. As new users experiment and familiarise themselves with online sharing, their appetite to share is at its highest. After all, there’s little point being in a social network if you don’t join the online conversation and share a little. But, for most people, this ego-driven desire to share can only be sustained if rewarded with reciprocal sharing or other motivating rewards. This is the value exchange in action. When we give something, we expect something in return, maybe not immediately but at some point in the future. As we learn how online sharing works, I believe many people grow disillusioned as they realise that the buzz of excitement they experienced during their initial sharing experimentation fades. When the value exchange is out of balance, when it’s all give and no get, our desire to share online weakens.

People share for different reasons. Sometimes we assume that everyone shares for the same motivations as our own, but humans are more complex than that. Some people share for altruistic reasons, others share to strengthen their relationships with others, and some people just share because they need someone to talk to. Everyone is different and we are influenced by changing motivations over time. Marketers who keep this in mind and can identity the most common motivations for sharing exhibited by their influencers will be better placed to create content they will be likely to share.

Creating sub-groups of friends is rare and looks set to stay that way. Today we typically share content with everyone in our social graph because, frankly, it’s the only easy way to do it. Services like Facebook and LinkedIn do provide facilities to categorise friends and send targeted content to different groups but doing this is time consuming and clunky. This explains why only 36% of people claim to have created subgroups, but 64% of people find the idea appealing. There’s a big problem here though: human relationships are fluid. Spending a few hours categorising a couple of hundred online friends today could prove to be largely wasted in six months’ time as relationships change and people require re-categorising into different groups. This relationship fluidity means that managing sub-groups becomes an on-going task. Even Google+, with its elegant circles interface, has been met by criticism for being too cumbersome and time-intensive. We need even simpler, more intuitive and self-updating mechanisms (where the computer takes away some of the maintenance burden) before categorising our friends will become commonplace on the web. And even then, I’m doubtful that humans will develop the ability to routinely maintain larger community groups than 150 contacts, as long prescribed in Dunbar’s Number.

Frictionless sharing, where your content is automatically shared with others, is here to stay. However, consumers will demand greater transparency and control over their sharing choices. Every time someone has a bad experience with frictionless sharing, like that embarrassing music track you listened to that has now been advertised to all your friends, the likelihood of their opting-in to future automated sharing is reduced.

My biggest worry with frictionless sharing is that the value of shared content conceptually reduces with every new piece of shared information. Of course, if you’re planning a meal out, it’s helpful to know that a friend enjoyed a meal in a local restaurant, but when hundreds of others have also shared similar information it becomes increasingly difficult to cut through the clutter and know who to trust. I sense we get a short-term buzz from seeing friend recommendations about the things around us, but when everyone starts sharing their views will the value we derive from this information remain as high?

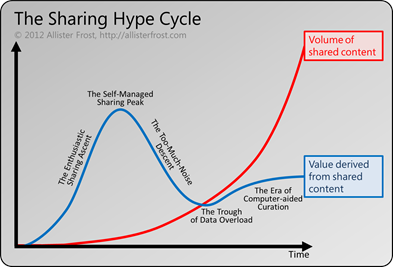

Here’s my take on how the value we will derive from shared online information may evolve as the volume of shared content rises exponentially:

It’s only after the initial buzz of excitement has faded—and we realise that more data is not always better data—that we’ll appreciate the need for improved computer-aided curation of information. These new tools will automatically amplify the visibility of our most trusted sharers and help us to ignore the less valuable data noise. Think Facebook’s Edgerank algorithm but for every piece of data in our lives…

And finally, the era of frictionless narrowcast sharing is approaching. As the sophistication of our online social networks grows, so will our appetite to selectively share specific content with very narrow sub-groups. During last week’s debate I cited the examples of sharing medical data in real time with your doctor or information about driving behaviour with motor insurance companies. These types of automated sharing, where the value exchange is fairly balanced between sharer and recipient, will become increasingly commonplace.

This is a fascinating area for future research. My thanks to Beyond for inviting me to join their panel debate and for sharing the research they conducted. See the links below for further reading:

-

Fishburn Hedges: To Share or not to Share?

Update: voting is open until 24 February for the Social Media Week Awards. Please vote wisely: http://chinwag.com/blogs/francesca-heath/vote-now-social-media-awards-2012-smwawards

Comments

One response to “The Future of Sharing: Social Media Week Panel Debate”

I like your Sharing Hype Cycle 🙂 It so seems that Social Stream Spam is here to stay. I’d a conversation today with a friend of mine on how to increase social sharing of brands/products, we ended up thinking that what we do is close to spam. To avoid that, increasing social sharing is not really the big problem, but improving and making your product offering relevant is the important part.